What sparked your interest in the history of the 1980 Turkish military coup?

The 1980 coup d'etat in Turkey is the defining event in the country's recent political history. The years leading up to it were marked by mass participation in urban political groups, as well as by a range of creative activist strategies aimed at revolutionising the city of Istanbul. Imagine a city characterised by the radicalisation en masse of students, workers and professional associations, precariously balanced between rival political forces and poised between different possible futures, even as its inhabitants charged into urban confrontation and polarisation.

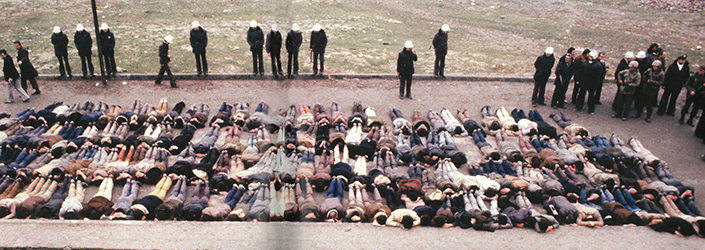

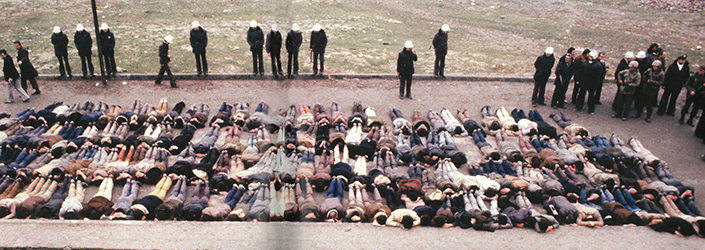

But then imagine a military insurrection. Total curfew. Flights in and out of the country suspended, a ban on theatre and cultural activities, schools and universities shut down. Books removed from library shelves that the new regime might found suspicious. ‘Wanted’ posters pasted at ferry terminals, civil police watching for suspicious responses. Whole suburbs targeted for ‘special treatment’.

These are the years examined in the book, significant not just in themselves but because the period of martial law that came after them (1980-1983) ushered in the new neo-liberal political economy in Turkey, as well as enshrining many constitutional changes that still structure Turkish politics.

What are you adding to the conversation about this event with your new book?

Over the last three decades there has been little detailed study about urban social movements and the broader practices and perceptions of activists and politically oriented civil society in Istanbul in the second half of the 1970s. Similarly, the lived experiences of activists and the mood of the city during three years of martial law have rarely been described, nor how that changed the spatial and social relations of its inhabitants. Indeed, we might say that there has been a ‘mass amnesia’ about the period, especially concerning the mass torture organised by the junta during the years of martial law.

So this book casts lights on a huge range of subjects and issues generally not known: for example, on the city’s political geography and its key sites of conflict and mobilisation; on violence as both spatial practice and generator of urban space; on militants’ perceptions of political fractions and of political ideologies; on the junta’s post-coup strategies for urban pacification; on contrasts in the socio-material structure and spatial organisation of Istanbul before and after the coup; and on the significance of activist practices and the coup for understanding the neoliberal ‘globalisation’ of Istanbul in the decades after.

How did you undertake the research for your book?

Alongside written sources, the key material analysed in this book derives from extensive interviews with ex-militants, which sought to facilitate autobiographical reflection upon their earlier selves and actions, and upon the city (and its places) that co-constituted them. Over a dispersed period from 2009 to 2014, I met with more than 50 people, men and women, from a variety of political organisations, including with militants from the violently anti-communist Nationalist Action Party (MHP). Often interviews would continue for a second session, as people remembered things they wanted to talk about.

Accordingly, Istanbul, City of the Fearless is also a study of memories. Even as ex-activists recounted ‘raw’ experiences from the time, certain memories were foregrounded, and others relegated to the ‘fringes’ of consciousness. In this re-assembling and new contextualising of past memories, I realised that telling is a performance.

What is the biggest misconception about this period in history?

It is not quite true to say that the 1970s in Turkey have not been written about or analysed. More precisely it is the complex and varied modes of activism, including consideration of the diverse practices, motivations, experiences, intentions and ethics of militants in the urban environment that has been simplified or ignored.

There is a large literature listing and explaining the context of events leading up to the coup. The best-disseminated account has been the discourse of the junta, broadcast (for years) after the coup in censored media space. Book chapters in general histories of ‘Modern Turkey’ often reference the picture of the 1970s sketched out by the junta, while work oriented to dependency and world-systems theory analyse the struggle over the political economy as a significant reason for social conflict.

So the biggest misconception about the period is the view propagated by the Turkish Armed Forces, which attributes responsibility for the military intervention to the collective anarchism, terrorism and class separatism of militants themselves. People still think that the coup 'happened' because of the activists, rather than because the military stepped in to re-structure politics.

What will readers be surprised to learn?

Most readers will be surprised to read about Istanbul - one of the great cities of the world - under the rule of the junta, and about what happened in the years immediately after the military insurrection, the junta’s spatial and activist politics, embarked upon to punish activists and to intimidate and pacify the city. They will learn about activists’ responses to this assault on Istanbul’s urban bodies and places. And they will be fascinated and appalled by the junta’s legal and institutional reconstruction of Turkish society, intended to drastically and permanently re-organise its political practices. Taken together the themes chronicle Istanbul’s shock entry into a reign of fascism and its preparation for a new authoritarian political and neoliberal economic order.

Ex-activists and others in the present continue to reckon with the meaning of those events. In particular the book shows how contemporary acts of urban commemoration by leftist political parties, unions, and civil society groups communicate to younger generations both the aims of their struggle and the losses accruing to its participants.

What's next for your research?

Things are a bit unclear now with travel restrictions, but Istanbul is endlessly fascinating, as are its urban developments. I'm hoping to kickstart a project examining the political history of the Golden Horn over the years of the Republic, one of the city's main industrial areas, including of labour movements.