The Flavians to the successors of Hadrian

Vespasian (69-79 CE) was the fourth (ultimately successful) of the contenders for imperial power after the death of Nero. His family was unrelated to previous emperors, and his veristic and craggy portrait shows off this difference. The new Flavian dynasty consisted of him, his son Titus, who succeeded him and ruled 79-81, and his younger son, Domitian.

Domitian (81-96 CE) succeeded his brother Titus ( 10 , 26 ). Under him Ephesus' provincial Temple of the Augusti was completed, where it is likely that all three Flavian emperors were worshipped. This gave Ephesus the title neokoros. Domitian, however, was not as popular with the Roman Senate as he likely was at Ephesus; he was eventually assassinated, and his name erased from many monuments.

Nerva (96-98 CE), an elderly and eminent Senator, was chosen to succeed Domitian. He had no sons, which precluded his founding a dynasty, but he cleverly adopted a powerful general, Trajan, and died in peace.

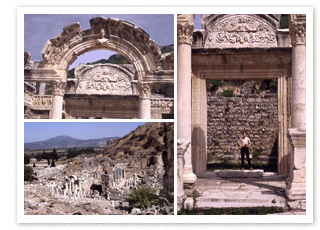

The temple of Hadrian on Curetes Street (the

Embolos). This small temple-like structure was

incorporated into the Varius Bath. It was dedicated

to Hadrian by P. Vedius Antoninus Sabinus.

Trajan (98-117 CE) spent most of his reign in successful wars to expand the borders of the Empire ( 27 ). Under him, the Roman Empire reached its greatest extent. He died on campaign against the Parthians, leaving the Empire to his grand-niece's husband, Hadrian.

Hadrian (117-138 CE) ( 8 , 15 ) spent most of his reign in traveling throughout the Empire. He sympathized with and spent much time in the Greek-speaking East, and especially aided the cities with honors and grants. He visited Ephesus frequently, and the city hailed him as another founder. He allowed three Asian cities, including Ephesus, to become neokoros by building a provincial temple for his worship. He had no children, so he adopted Antoninus Pius to succeed him. Ephesus, now headquarters of the governor of Asia, was often honored with the visits of emperors; Hadrian came through several times.

Antoninus Pius (138-161 CE) did not travel as Hadrian had, but before his adoption he had served as proconsul of Asia, so he must have known Ephesus well ( 28 ). As Emperor, he personally sent a letter to the city regarding its quarrel with Smyrna and Pergamon over titulature (see Ephesus and its neighbours), and Ephesus had this letter copied and set it up proudly in public.

Marcus Aurelius (161-180 CE), adopted son of Antoninus Pius, is best known for writing his philosophical Meditations ( 13 , 29 , 30 ). A war with Parthia broke out early in his reign, and he sent his adoptive brother and co-ruler Lucius Verus to the East to deal with it. Verus visited Ephesus, and was even married there; his Parthian war, and later apotheosis, became subjects for the sculpture of a great monument in the city, the so-called Parthian Monument.

Commodus (180-192), though son and successor of Marcus Aurelius, was more interested in horse races and the games in Rome than in philosophy ( 1 ). His assassination in 192 led to a period of confusion in the Empire, with many contenders for power.