In conjunction with Macquarie University History Museum's display "The Olympic Games Past and Present" Dr Keith Rathbone, Senior Lecturer the Department of History and Archaeology explains how the ancient Olympics are deeply infused in the modern Games.

When the Paris Olympics and Paralympics open in July 2024 and August 2024, athletes will compete in almost forty sporting venues across the country. These venues were not only selected for their amenity or location: their historical resonances also played a role. Underneath the Eiffel tower, Olympians will play beach volleyball. At the Chateau de Versailles, Equestrian and Pentathlon stars will perform in front of a new temporary grandstand. On the Place de la Concorde, at the end of the Champs Élysées, Olympians will compete in breakdancing (new to the 2024 Games, with Macquarie University’s Rachael Gunn appearing for Australia), BMX, and 3x3 basketball. The French Olympic committee won their bid by using a lexicon that the International Olympic Committee appreciated and understood. The French committee sold the value of Paris’ history and their ability to make that history modern. The IOC too puts history at the centre of their Modern Games, and it remains fundamental to our appreciation and understandings of them. (Image: Olympic rings in the Place du Trocadéro in Paris. Photo Anne Jea, Wikicommons)

The Ancient Olympics were a religious festival devoted to the god Zeus that grew into a massive celebration of Greek identity. At their height, the Games welcomed tens of thousands of athletes and spectators every four years to the city of Olympus. The Ancient Games persisted for a millennium – the first contest was held c. 776 BCE and it continued in some fashion at the same site until 393 CE. During the Games, Greek city-states agreed to allow competitors and spectators to travel to Olympia from around the Peloponnese and further unmolested despite rivalry and war. While this agreement did not formally end all fighting, indeed at one point there was a fight inside of the sanctuary during the Games, the idea formed the basis of the Olympic Peace.

The Roman emperor Theodosius I reputedly banned the original Olympic Games because they were a pagan festival, but another millennia later, growing interest in classicism among Europeans, beginning in the Renaissance, led to a revival of curiosity in Greek physical culture. In 1776, the English antiquarian Richard Chandler rediscovered Olympia, which had been left to ruin. From the 17th century, European sportsmen organized athletic competitions under the name of the Olympics, including the Cotswold Olimpick Games, the Olympiade de la Republique, and the Wenlock Olympic Games. In 1859, in the wake of the Greek War of Independence, the Greek government supported a revival of the Games in Athens and at the end of the 19th century German archaeologists and the Greek government together began the first digs on the Olympia site.

(Image: Temple of Zeus at Olympia (Toppled ruins). Photo: Michael Nicht, Wikicommons)

In the context of growing fascination with, and knowledge about, the Ancient Games, Pierre de Coubertin, a French aristocrat, educator and historian, founded the International Olympic Committee in 1894. De Coubertin believed that physical education could generate healthy bodies, minds, and spirits and he was inspired by the legacy of the Ancient Games' athletes and also by both the modern sporting movement in Great Britain and the popular gymnastics trends that were taking over the continent. In 1894, de Coubertin hosted the first Olympic Congress, in Paris where a gathering of around delegates from around Europe agreed to revive the Olympic Games. From the very beginning, the IOC had loftier (if also more worldly aims). The IOC adopted the express goal of fostering peace among nations and not only to ensure the security of the Games. De Coubertin noted that “Athletics can bring into play both the noblest and the basest passions … they can be used to strengthen peace or to prepare for war.” That implicit tension has both bolstered and troubled the Olympic movement since its modern reformation.

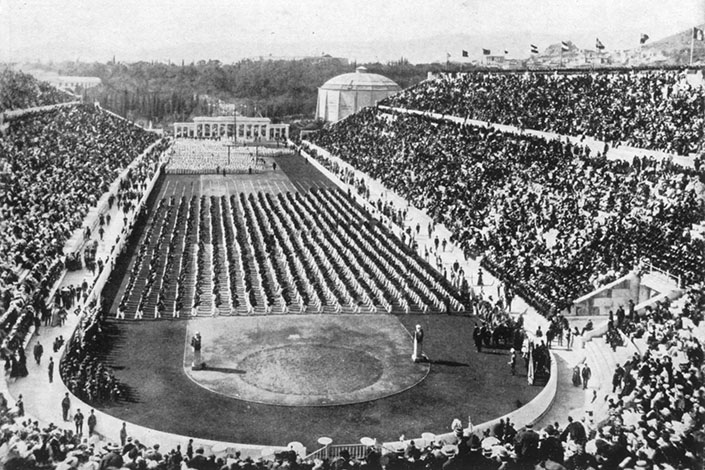

The founders of the Modern Olympics were aware of the longer history of Olympic competition and deliberately modelled their Games as a reflection of the Ancient Olympics. In doing so, they hoped to align their competition with the prestige of the Ancients, and to establish a distinction between the IOC and other international sporting movements such as the nascent workers sporting movement. They hosted their first contest in Athens, in large part funded by the Greek government. They also took on the trappings of the Ancient Games and modelled some of their celebrations, including the lighting of the Olympic torch, on their understandings of celebrations held by the Hellenes. For example, winners of the gold medal also receive an olive wreath, traditional symbol of the winner of the Ancient Olympic Games.

(Image: Panathenaic Stadium, during the Athens 1896 Olympic Games. Hulton Archive/Getty Images. Encyclopædia Britannica)

The International Olympic Committee’s Modern Games reflected not only the influence of classical culture, but also spoke to the organizers’ interest in their contemporary elite internationalism. The Ancient Games were welcome to men of all social classes. In fact, the first Olympic champion Coroebus was a baker (and evidently also a fast runner.) The Modern Olympics were initially an elite affair. The limitation of competition to amateurism meant that most of the sportsmen were well-off. At the same time, the Modern Olympics also aimed to be more cosmopolitan than the Ancient Games. The interlocking rings represent the Games’ global ambitions; the five rings represented the five continents. The institution of gold, silver, and bronze medals represented de Coubertin’s emphasis of struggle over the singular virtue of victory.

In other words: the Modern Olympics mirrored some of the values of the Ancient Games, but they usually did so imperfectly, and the Modern Games were also shaped by contemporary cultural movements. For example, the organizers revived many ancient competitions but again added their own too. Ancient Olympians competed in athletics, boxing, chariot racing, mixed martial arts (a sport called Pankration), and wrestling. The founders of the Modern Olympics revived many of these competitions in the 19th century, except for chariot racing and Pankration, but they also added their own competitions. In the 1896 Athens Olympics, athletes competed in athletics, cycling, fencing, gymnastics, shooting, swimming, tennis, weightlifting, and wrestling. They occasionally cloaked modern sports with faux ancient pedigree. For example, the marathon was a race meant to celebrate the victory of the Greeks over the Persians in 490 BCE. The Greek Pheidippides supposedly ran from the battlefield at Marathon to Athens to announce the Greek victory (only shortly afterwards to collapse and die). In fact, Pheidippides’ run is highly contested. The organizers of the marathon in 1896 built the race around a British poem; Pheidippides by Robert Browning. In other words, rather than a reintroduction, the first marathon was an invention of the Modern Olympics.

(Image: The drama of ancient chariot racing is captured on the surface of this black-figured kylix, included in the display "The Olympic Games Past and Present" (MU3231 Photo: Effy Alexakis, PhotoWrite)

In the century plus following the foundation of the Modern Olympics, many things have changed to make the Games more contemporary to the 20th and 21st century. An ancient Greek person brought to the present might be surprised that in the Modern Games athletes generally wear clothing – and women compete and excel in the full slate of events. Women fought to compete in the Games from the very beginning – even staging their own women’s only counter-Olympics – and in response the IOC admitted them to the full slate of sports from the 1924 Paris Games onward. The competitors are also no longer only Greek (or later Greek speakers) but encompass people from every corner of the globe. The Games also no longer take place every four years in Greece. They are now hosted in metropolises around the world and broken into Summer and Winter competitions run on a biannual schedule. (Image: Australian athletics competitor Louise Sauvage lights the cauldron with the Paralympic Flame at the finish of the torch relay, 2000 Sydney Paralympic Games Opening Ceremony. Photo: Wikicommons).

The kinds of games Olympians compete in are very different and reflect the popularity of new sports such as basketball, football and rugby. Disciplines have entered and left the Olympic schedule: jeu-de-paume, polo, roque, tug-of-war are gone, while golf and rugby have returned to the schedule (and cricket and lacrosse will do in 1928 in Los Angeles.) The Modern Olympics also used to award medals for art, including for architecture, literature, music, painting, and sculpture. Pierre de Coubertin once won a medal for poetry. Non-athletic competition ended in the 1950s. In Paris 2024, four new sports will appear: breakdancing, skateboarding, surfing, and rock climbing.

One of the closest parallels between the Ancient and Modern Games might be that of the spectators. While people today can enjoy the Games on television (or from their cell phones), the Ancient Olympics was primarily an in-person experience. Up to 40,000 spectators converged on Olympia from across the Greek world. The spectators were mostly men (although debate remains whether unmarried women were also allowed to watch). For five days, the fans enjoyed the competitions, ate prodigious amounts of meat, purchased souvenirs of their trip, and rallied support for their city-states. Indeed, the Ancient Games were a space of deep political contestation, sublimated through athletic competition. The exuberance of the stadium in the Modern Games sounds very similar.

The Macquarie University History Museum’s exhibit showcases many of these major themes: the exertion of muscled athletes and dancers, the extasy of victory, the support of spectators and states, and the continual commercialization of the Games. Pierre de Coubertin and his contemporaries revived the Olympic Games in celebration and recognition of the Ancient Games even as they hoped to supersede them. The Modern Games, however, have always been limited by the same tension of the Ancient Games between the romantic goals of the organizers and the national (or civic) pridefulness of the competitors and spectators. As Pierre de Coubertin must have known: plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose (the more things change, the more things stay the same).

Dr Keith Rathbone (Ph.D., Northwestern University, 2015) is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of History and Archaeology at Macquarie University. He researches twentieth century French social and cultural history.