This article was originally published by Jane Messer on The Conversation, and shared as part of the Creative Commons.

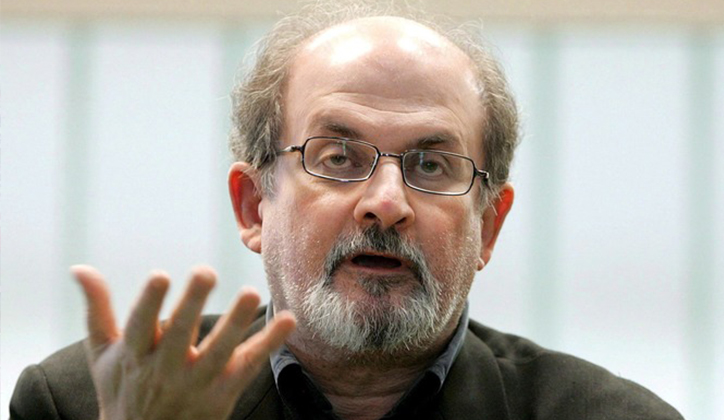

Poor Salman Rushdie. On the global books site GoodReads, he recently gave public 1-, 2- and 3-star ratings to books by well-known and esteemed writers such as Kingsley Amis, the late father of his friend Martin Amis, and Hermione Lee.

He claims not to have realised his ratings were public.

GoodReads – launched in 2007 – is now, internationally, the most-read site for book reviews and book ratings, with more than 20 million published reviews in 2012 and a more recent claim to have reached 34 million.

Charlotte Durack, Marketing Executive at Pan MacMillan Australia, told me recently that it is the most important site at which authors should have a presence, “as this is where the majority of reviewers live”.

Social media is a whole other universe to the writing of long-form novels and nonfiction. Essentially un-gated, it offers writers the chance to directly engage with readers and the industry about their political or cultural interests, their writing activities, new books and favourite reads or restaurants.

It is instant, viral, and it never forgets. And it’s an arena in which many writers struggle to learn the rules of combat, and how to represent themselves to the world at large.

Rushdie claimed he was a social-media innocent following the GoodReads incident:

I’m so clumsy in this new world of social media sometimes. I thought these [GoodReads] rankings were a private thing […]. Turns out they are public. Stupid me.

Rushdie is in fact a well-practiced social media intemperate. He has a long history of using Facebook, email and Twitter. Sometimes for good: he’ll campaign for human rights and political justice issues, for instance.

He can also be argumentative on Twitter, seemingly unable to resist a retort to any facile tweet. And he uses social media to flirt, seduce or withdraw, in very public ways.

Some of the women he has courted are more assiduous with their social media skills than him: to wit, American actor Devorah Rose’s 2011 retaliation to his public rejection of her, after the two were linked romantically.

Star system

The negative reaction by other authors to Rushdie’s book ratings demonstrates how sensitive writers can be to the public discussion of the literature of their peers or literary antecedents. But why shouldn’t an author as reader, or expert reader, give however many stars they like to a book?

The star system can be glib and offhand when not accompanied by a cogent review. There are no ethics guidelines or even tips or warnings that I could find on GoodReads to guide reviewers about this. Amazon, however – which bought GoodReads in 2013 – has a comparatively detailed policy, which includes the What’s Not Allowed direction to not publish:

Sentiments by or on behalf of a person or company with a financial interest in the product or a directly competing product (including reviews by publishers, manufacturers, or third-party merchants selling the product.

Amazon’s policy didn’t deter British historian Orlando Figes from commenting on competitors’ books. In 2010 he admitted to being the author of scathing customer book reviews on the site.

He’d been outed by the Times Literary Supplement after posting a suspicious spate of bad of reviews of other historians’ works under two foolishly transparent nick names: “orlando-birkbeck” and “Historian”.

As Rushdie might have said of Figes: “Stupid him”.

The literary community is the writer’s workplace, and readers their customers. In other spheres of industry, workers mostly won’t openly criticise a colleague’s skills, and risk their ire, the loss of a friendship, or other repercussions too unbearable to contemplate.

And yet, writers and book reviewing and criticism are different because of the responsibility to speak courageously when speaking publicly.

A range of new Australian awards, prizes and review sites are encouraging just this. They include the Sydney Review of Books, the Australian Women’s Writers Challenge, and the Pascal Prize for Australian Critic of the Year.

These relatively new initiatives are having influence and impact, by expanding the depth and range of reviews of books and writing, and a diversity of reviewers, among whom are authors.

And yes, authors – such as myself – inevitably have a potential conflict of interest when reviewing the work of even distant associates. For this reason, many avoid reviewing.

But, even a quick glance back shows that when it really matters, authors and critics speak up loudly. It happened with Helen Demidenko’s The Hand that Signed the Paper (1994), and Helen Garner’s The First Stone (1995).

Significant problems were identified relating to the writing of those works.

Writers certainly leaped to the defence of Frank Moorhouse’s Grand Days (1993) after it was rejected by the Miles Franklin Award judges in 1993 for not satisfying the criteria of being sufficiently enough about “Australian life”.

When the stakes are high, many authors will speak truth to power. The more diverse the review sites, print and online, the more confident authors can be that their evaluation of another author’s work is being offered within a robust context of critique.

The Washington Post took the angle that the Rushdie incident was an issue of poor user understanding of public/private settings. Rushdie stepped down as a reviewer from GoodReads, admitting he hadn’t got that aspect of the site. A great many people tweeted and republished The Independent’s story.

Say something indefensible, have a change of heart, diss another writer’s work on a bad day: well, a whole lot of people are going to know it. My take-away? Authors need to be very digitally literate to make the best use of their voices.

Catch up on recent contributions to The Conversation from other Macquarie authors.