Related Histories: Studying the Family Conference

The Related Histories: Studying the Family Conference was held at the National Library of Australia in Canberra on the 28 and 29 November 2017. The conference brought together a variety of amateur and academic scholars to discuss the ways in which we create and share histories of the family.

Post by Caitlin Adams.

Stephen Foster

opened the first session of the Related Histories conference by asking: is family history a genre? Over the next two days, and throughout the presentations, it was clear that there are not distinct boundaries between family history, and other histories or historical practices.

This was seen in the diversity of attendees, who ranged from academic scholars, to independent researchers, family historians, archivists, history students and early career researchers. Yet while this audience was diverse, I felt that there was a definite sense of shared purpose. Attendees

animatedly swapped anecdotes of archival research, or startling discoveries over tea and coffee during the breaks, and chuckled appreciatively when presenters talked about reaching ‘dead-ends’ in their research. Indeed, when

Cheney Brew

from the National Library of Australia asked who had used Trove, the entire room raised their hands.

The National Library of Australia.

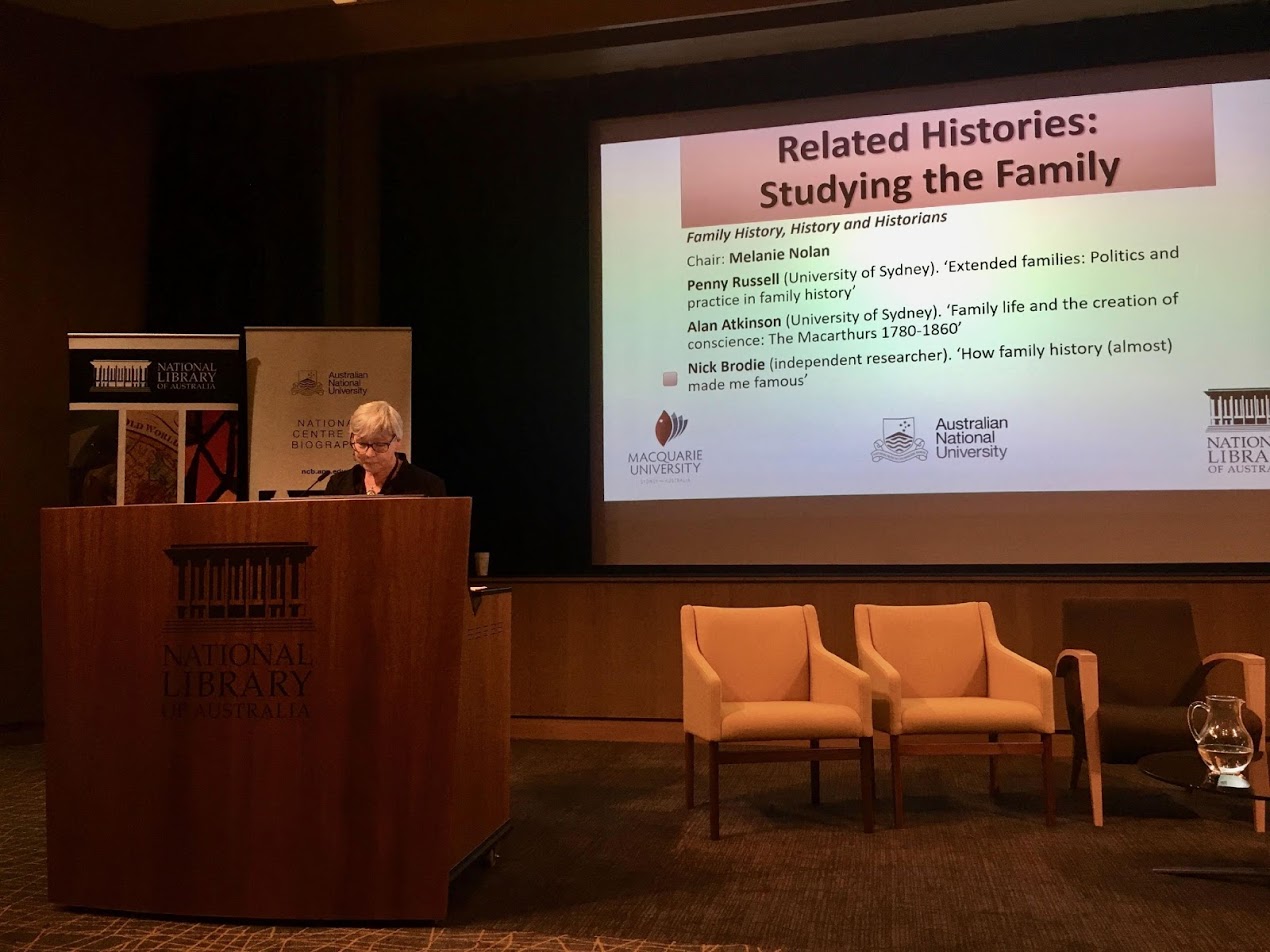

This sense of shared purpose was certainly fostered by the conference organisers. In her opening remarks,

Melanie Nolan

emphasised the importance of collaboration, and attendees were all invited to join a Family History Research Network initiated by the National Centre for Biography at the Australian National University and the Centre for Applied History. Presenters also emphasised the need for partnerships between

academic and family historians.

Kate Bagnall

and

Barry McGowan

both argued that family historians and volunteers were essential to their research into the experiences of Chinese families in Australia. Kate was also passionate about the need to freely share research, recounting a moving story about how her findings have changed people’s lives.

Kate Bagnall showcases her Australian Hometown Heritage Tour that she runs to China.

The idea that academic and family history are both part of a shared set of practices was also clear throughout the presentations.

Cathy Day

used family history techniques in her research into cousin marriage in Wiltshire, England, while Angela Wanhalla used similar techniques to explore the ways in which American servicemen influenced the lives of Indigenous families living in the South Pacific. Other presenters, including

Tim Bonyhady

,

Shauna Bostock-Smith

,

Helen Morgan

,

Babette Smith

, and

Nick Brodie

shared parts of their own family history, and its role in inspiring and shaping their academic research.

Research practice was another key concern of the conference, with several presentations featuring practical tips for using databases, finding archival material and publishing family histories.

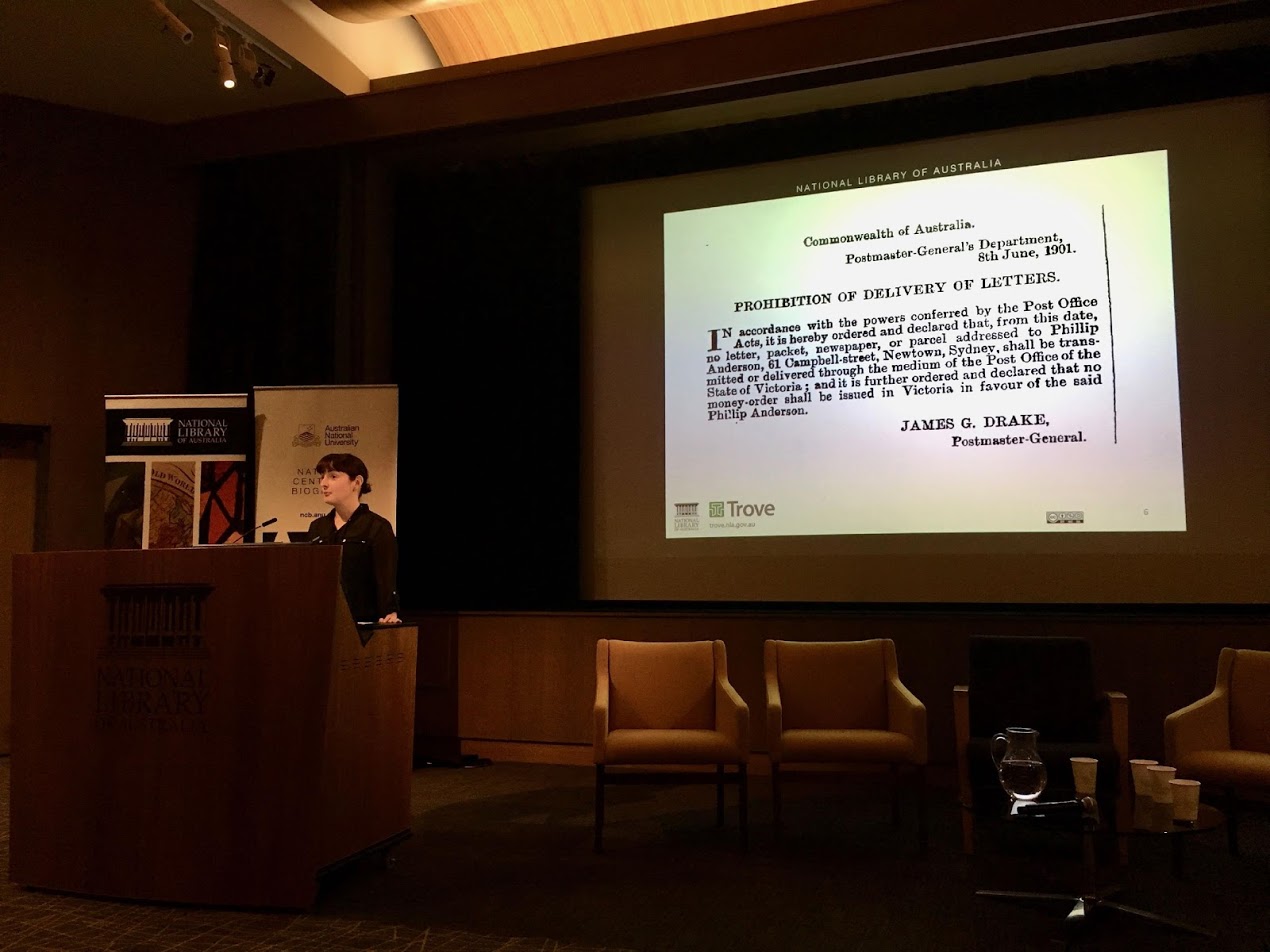

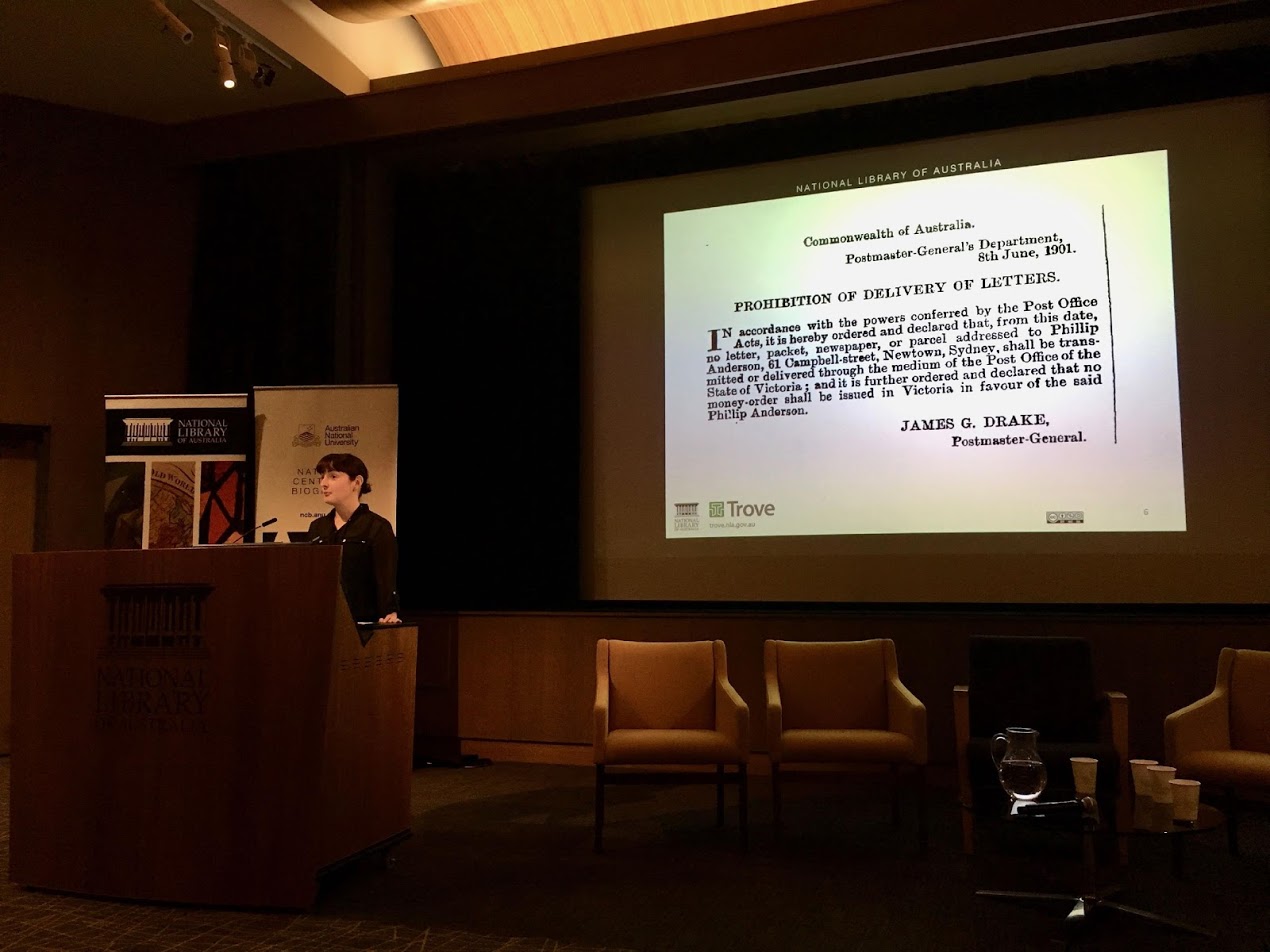

Cheney Brew

from the Trove team at the National Library gave a practical demonstration on how to search Government Gazettes, while

Gina Grey

, from the National Archives of Australia, presented an engaging example of how to transform original records into a rich narrative history. Similarly,

Christine Fernon

and

Scott Yeadon

from the National Centre of Biography demonstrated how to use the links and networks within the Australian Dictionary of Biography, and showcased their initial findings of their ‘First Fleets’ project.

Gail White

and

Martin Playne

from the Australian Institute of Genealogy and Genealogical Society of Victoria respectively, provided advice for how to publish your family history, and win awards while doing so. For those seeking lengthier training,

Kristyn Harman

gave us a tantalising taster of the University of Tasmania’s Diploma of Family History.

Cheney Brew explores Government Gazettes.

Other talks examined the complexities of family history research.

Simon Easteal’s

talk on genetics demonstrated that a tree is not the best way to represent relatedness, and challenged us to re-think how we understand what the family is.

Anna Green

also prompted us to think about family history in greater complexity, as she explored the ways in which people understand the past through family stories. Similarly,

Susannah Radstone

explored the ways in which memory studies can complement the approaches of family historians.

Another key concern throughout the presentations was the ways in which family histories, or histories of the family, are intertwined with broader historical contexts.

Penny Russell

gave an engaging talk about the ways in which her family history could not be divorced from its context within settler colonialism, and how this might influence the practice of the family historian.

Alan Atkinson

used the history of the Macarthur family to explore the ways in which families create a shared sense of subjectivity and conscience. Likewise,

Janet McCalman

explored the ways in which wars, booms and busts could influence individual families, and their ability to survive. On the other hand,

Anna Clark

and

Jane McCabe

explored the ruptures between family history and national histories. Anna’s research found that while ordinary people felt connected to their family’s past, they did not always feel part of national narratives. Similarly, Jane found that some family histories simply do not ‘fit’

into stories that nations tell about themselves.

Penny Russell discussing the experiences of her Thompson ancestors.

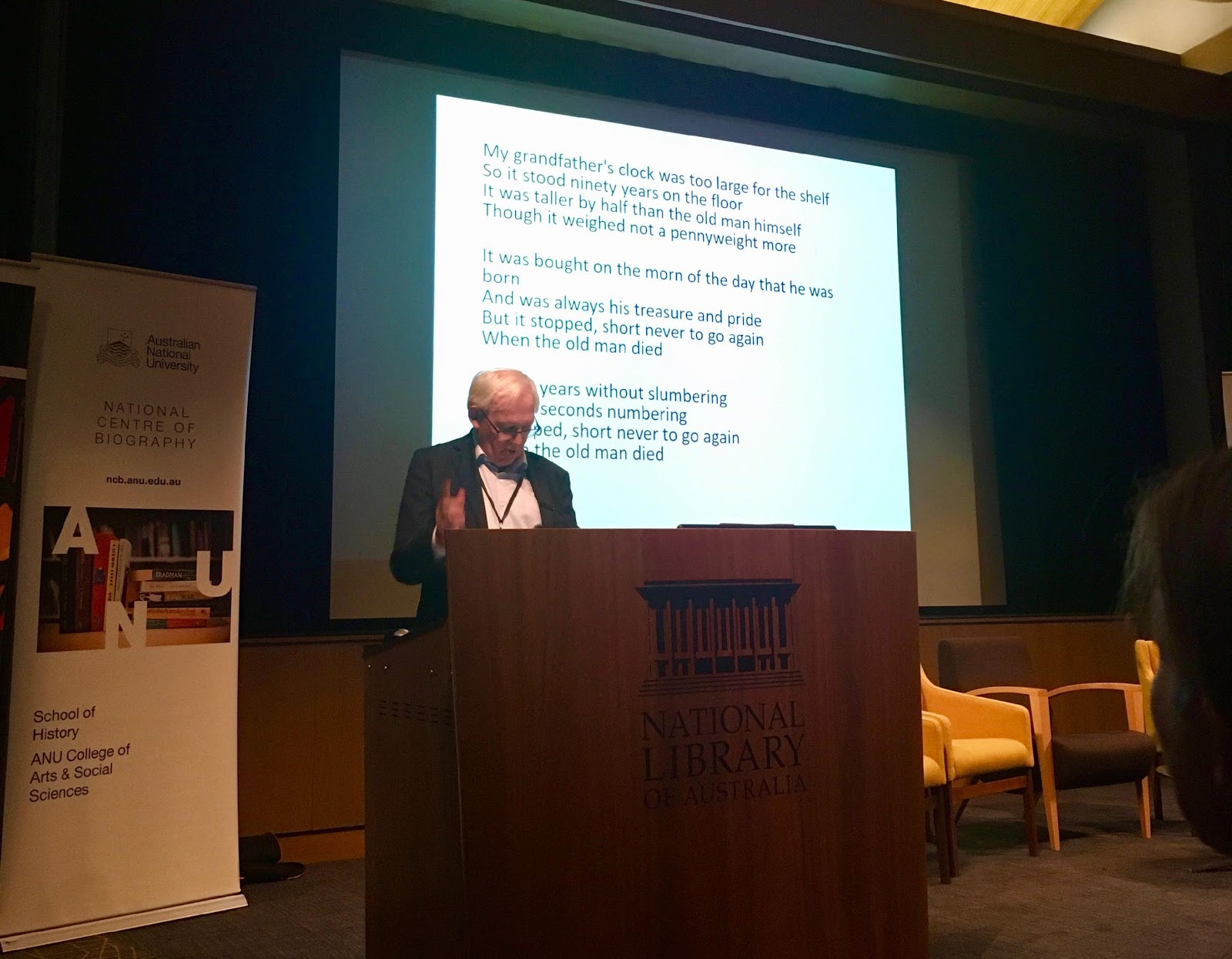

Graeme Davison

, who gave the keynote lecture, also explored the ways in which family histories connect to broader contexts and social trends. Taking a family heirloom — his Grandfather’s clock — he traced his own family history, exploring how the Davisons had been influenced by the Industrial Revolution,

Chartism and migration to Australia. A particular highlight from Graeme’s lecture was when he led an enthusiastic audience in singing “My Grandfather’s Clock.” A moving moment for all involved.

Graeme Davison leading the audience in song.

Finally, presenters argued that family history can transform society.

Emma Shaw

explained that family history was a form of public pedagogy, as family historians educate themselves by acquiring new knowledge and skills.

Jenny Hocking

noted that political biographies can challenge and reshape historical knowledge and understanding. And the Centre for Applied History’s Director,

Tanya Evans

, concluded the conference by arguing that family history makes people better citizens — it can literally change the world.

It was a fabulous and jam-packed two days, and attendees departed in a flurry of excited chatter. It was clear that we had all been inspired, challenged, and had formed new collaborative networks. While many speakers remarked that digital tools make research easier, they also demonstrated

that the stories we create remain complex and contested— prompting discussions about the need to be critical and sensitive in our research. Thus, the conference equipped us to be better practitioners, yet more fundamentally, it fostered partnerships between researchers from a variety of backgrounds

and interests.

Caitlin Adams